荷兰海牙,7月12日 —— 一份由“世界公民法庭”(The Court of the Citizens of the World)公开发布的文件显示,该机构宣布对中华人民共和国主席习近平发出逮捕通告,指控其在西藏和新疆地区实施了包括反人类罪和种族灭绝罪在内的严重罪行。这一通告在国际舆论中引发了关注与讨论。

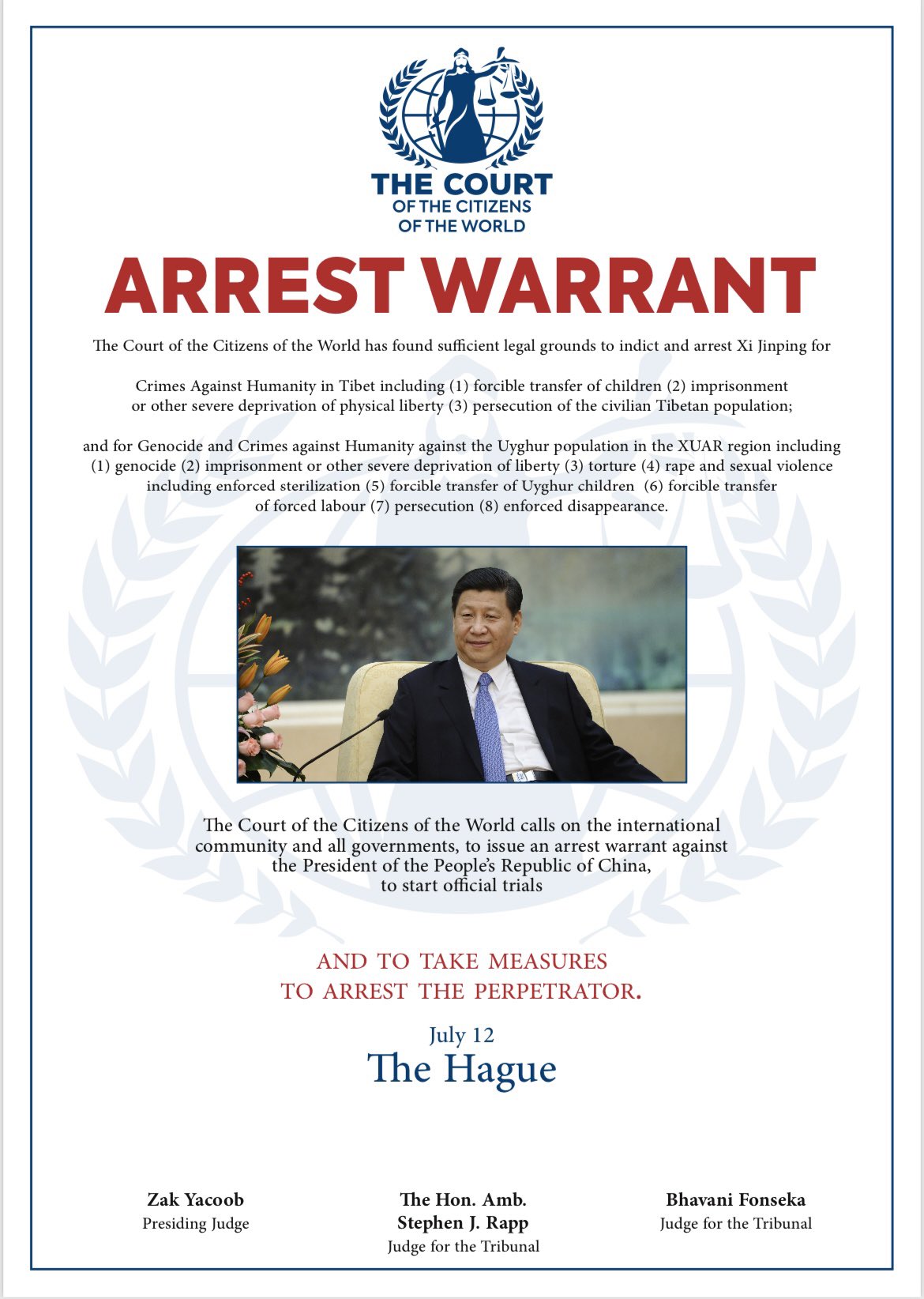

通告标题为 “Arrest Warrant”(逮捕令)。文件写道:“世界公民法庭已经找到充分的法律依据,正式起诉并要求逮捕习近平。”

通告将相关罪行分为两部分:

在西藏的罪行

文件指控习近平在西藏地区涉及三项主要罪行:

- 强迫转移儿童(forcible transfer of children)

- 监禁或严重剥夺人身自由(imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty)

- 对平民藏人群体的迫害(persecution of the civilian Tibetan population)

在新疆的罪行

文件列举了针对维吾尔族群体的八项罪名,归类为“种族灭绝与反人类罪”:

- 种族灭绝(genocide)

- 监禁或严重剥夺人身自由

- 酷刑(torture)

- 强奸与性暴力,包括强制绝育(rape and sexual violence including enforced sterilization)

- 强迫转移维吾尔儿童(forcible transfer of Uyghur children)

- 强迫劳动(forced labour)

- 迫害(persecution)

- 强迫失踪(enforced disappearance)

诉求与行动呼吁

通告明确呼吁:

- 国际社会与各国政府应 签发正式逮捕令;

- 应采取措施 拘捕中华人民共和国主席习近平;

- 应启动 正式的司法审判程序。

文件强调,这是为了应对“针对维吾尔族和藏族人民所发生的大规模反人类罪行”。

该逮捕令由三位署名法官签署:

- Zak Yacoob —— 首席法官(Presiding Judge)

- Stephen J. Rapp —— 法官,前美国驻国际刑事法庭大使

- Bhavani Fonseka —— 法官,人权律师

文件末尾注明日期为 7月12日,发布地点为 荷兰海牙。

背景与相关资料

“世界公民法庭”自称为一个由国际人士组成的“公民法庭”,不属于联合国,也不隶属于国际刑事法院(ICC)。该机构的定位是以“公民社会”为主体,通过象征性的审判与文书,推动全球舆论与各国政府重视人权问题。

该逮捕令所涉及的指控,与近二十年来国际社会对中国人权状况的关注高度一致:

- 新疆问题:

从2017年起,媒体与人权组织多次披露新疆存在大规模的“再教育营”或“拘押营”,关押人数可能超过百万。国际调查报告指出,相关政策包括强迫劳动、大规模监控、文化同化、限制宗教信仰、强制绝育和对未成年人的强制隔离教育。

2022年,联合国人权事务高级专员办事处曾发布报告,表示中国在新疆的行为“可能构成反人类罪”。 - 西藏问题:

近年来,关于西藏的报道集中在“寄宿学校”制度。多份国际研究指出,数十万藏族儿童被迫离开家庭进入寄宿学校,接受以普通话和中共政治宣传为核心的教育,这被批评为“文化同化政策”。与此同时,当地宗教自由依然受到严格限制。

国际法专家指出,这些行为可能符合《防止及惩治灭绝种族罪公约》(1948年)的若干条款。

目前,国际主流媒体对这份逮捕通告有所报道,但也指出其法律效力存在限制。由于“世界公民法庭”并非联合国机构或国际刑事法院,其文书不具备直接的司法强制力。

然而,文件的公开发布被视为一个象征性举动,意在:

- 向国际社会强调中国人权议题的严重性;

- 以“逮捕令”的形式引发更广泛的公众与政治关注;

- 对各国政府施加压力,促使其在外交和政策层面采取行动。

“世界公民法庭”在海牙发布的逮捕通告,指控习近平在西藏与新疆实施了涉及种族灭绝与反人类罪的多项罪行。文件虽然缺乏国际法上的直接效力,但内容涉及的问题与国际社会长期关注的中国人权议题高度一致。这一事件为全球关于中国人权问题的持续讨论增添了新的焦点。

The Court of the Citizens of the World Issues Arrest Warrant Against Xi Jinping in The Hague

The Hague, July 12 — A document released by the Court of the Citizens of the World announced that the institution has issued an arrest warrant against Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, accusing him of committing crimes against humanity and genocide in Tibet and Xinjiang. The announcement has drawn attention and debate in international public opinion.

The document, titled “Arrest Warrant,” states: “The Court of the Citizens of the World has found sufficient legal grounds to indict and arrest Xi Jinping.” The warrant divides the alleged crimes into two parts, relating to Tibet and Xinjiang.

In Tibet, the warrant accuses Xi Jinping of three major crimes: forcible transfer of children, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty, and persecution of the civilian Tibetan population.

In Xinjiang, the warrant lists eight charges against the Uyghur population, categorized as genocide and crimes against humanity. These include genocide, imprisonment or severe deprivation of liberty, torture, rape and sexual violence including enforced sterilization, forcible transfer of Uyghur children, forced labour, persecution, and enforced disappearance.

The document calls on the international community and governments to issue an official arrest warrant, to take measures to arrest Xi Jinping, and to initiate formal judicial proceedings. It emphasizes that these steps are necessary to respond to large-scale crimes against humanity committed against the Uyghur and Tibetan peoples.

The arrest warrant is signed by three judges: Zak Yacoob, Presiding Judge; Stephen J. Rapp, former U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues; and Bhavani Fonseka, human rights lawyer. The document is dated July 12 and specifies The Hague as the place of issuance.

The Court of the Citizens of the World describes itself as a “people’s tribunal” composed of international figures. It is not affiliated with the United Nations or the International Criminal Court (ICC). Its mission is to use symbolic trials and legal documents to encourage public awareness and governmental attention to human rights issues.

The allegations in the warrant align closely with concerns that have been raised internationally for years regarding China’s human rights record. In Xinjiang, since 2017, media and human rights groups have reported the existence of large-scale “re-education camps” or detention centers holding possibly more than one million people. Reports have documented forced labour, mass surveillance, cultural assimilation, restrictions on religion, forced sterilizations, and the separation of children from their families. In 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that China’s actions in Xinjiang “may constitute crimes against humanity.”

In Tibet, international research has pointed to the widespread use of boarding schools, where hundreds of thousands of Tibetan children have been separated from their families and placed in state-run schools, taught primarily in Mandarin and exposed to political indoctrination. This practice has been criticized as cultural assimilation, while restrictions on religious freedom remain severe. Legal experts have suggested that these policies may fall under several provisions of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

International media outlets have reported on the arrest warrant, noting that its legal effect is limited. Because the Court of the Citizens of the World is not an official UN or ICC body, its documents do not carry binding enforcement power. Nevertheless, the warrant is seen as a symbolic act intended to highlight the seriousness of human rights issues in China, to draw wider public and political attention, and to increase pressure on governments to respond through diplomacy and policy.

The arrest warrant issued in The Hague accuses Xi Jinping of committing genocide and crimes against humanity in Tibet and Xinjiang. Although it lacks formal legal force, the allegations echo longstanding concerns raised by international observers and human rights groups. The publication of the document adds a new point of focus to the ongoing global discussion on human rights in China.